The plate arrived already damaged. Paul Scott orders vintage transferware online — pieces that sellers photograph apologetically with cracks running through Romantic landscapes and chips interrupting Willow Pattern bridges. Yet he wants them broken. Caroline Slotte, his former student at the Bergen Academy of Art and Design, works the same way. Both artists treat 19th-century blue-and-white ceramics as readymade canvases, but their interventions diverge. Scott collages contemporary disaster onto pastoral fantasy, while Slotte sandblasts until the past becomes vapor.

One Way or Another, on view through Feb. 28, 2026, at HB381 Gallery in New York, pairs the two artists in a dialogue about how to dismantle inherited images. The exhibition takes its conceptual anchor from transferware — those mass-produced plates depicting sanitized versions of colonial encounters, picturesque ruins or Orientalist fantasy. Scott and Slotte both recognize these objects as repositories of cultural mythology. Their project is both archaeological and surgical: excavate the ideology, operate on the surface.

Scott’s “New American Scenery” series updates the genre of American transferware that Staffordshire factories exported in the 1800s. Where those originals depicted idyllic views of young republic monuments, Scott superimposes images of Standing Rock protests, California wildfires and Detroit’s industrial collapse. His “Broken Treaties” plates layer Ryan Vizzions’ photograph of a Lakota woman on horseback confronting militarized police over Benjamin West’s fabricated painting of William Penn’s treaty ceremony. The collision is deliberate. Scott forces the fantasy to acknowledge what is erased.

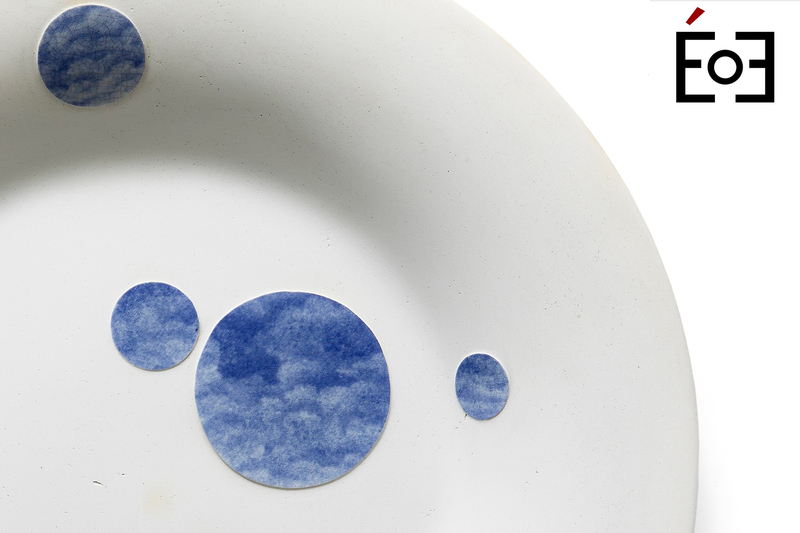

Slotte takes the opposite approach; she removes instead of adding. Using stencils and sandblasting equipment, she deletes elements from Blue Willow and Wild Rose patterns until only the atmosphere remains. Her “American Skies” series preserves clouds and negative space, eliminating architecture, figures and narrative. What’s left reads like memory after trauma; the gaps where detail should be. Design historian Glenn Adamson calls it “a strange sort of craft, consisting as it does almost entirely in deletion.”

Both artists repair their altered plates using kintsugi, the Japanese practice of mending ceramics with lacquer and gold leaf. The technique refuses to hide damage. Scott’s gold lines trace where plates shattered in shipping. Slotte’s repairs accentuate structural vulnerability. The kintsugi becomes a compositional element, drawing more attention to the object’s history of use, breakage and transformation. Imperfection is not a flaw but evidence.